One thing I’ve learned over the past year is that a lot of people don’t understand money flows and the differences between negative, zero, and positive sum games. If you’re going to invest in any sort of asset, or trade any sort of market, you need to know how money is flowing through it. You need to understand the game you’re playing.

You need to understand the game you’re playing

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Expectancy

- Positive Sum Game

- Real Life Examples

- Zero Sum Game

- Real Life Examples

- Negative Sum Game

- Real Life Examples

- Know What You Own

Expectancy

First, to understand positive/zero/negative sum games in the markets, we need to talk about expectancy. Expectancy is very simple…it’s the average profit or loss an investor or trader can expect to make. To calculate expectancy among a group of investors, all we need to do is take their net profit/loss as a group and divide by the number of investors. There will be a net profit if it’s a positive sum game, net zero if it’s zero sum, and net loss if it’s negative sum. Thus, an investor will, on average, make money in a positive sum game, make nothing in zero sum game, and lose money in a negative sum game.

- Positive sum game. The amount of money flowing out to investors is greater than what investors put in. There is a net profit. Thus, an investor will make money on average. There is a positive expectancy. That doesn’t mean every investor makes money. Some may actually lose money. It just means that investors make money on average.

- Zero sum game. The amount of money flowing out to investors is the same as what investors put in. There is no net profit or loss among the group. Thus, any winning investor is paid out by a losing investor. Even if you have some winners, the expectancy (the average profit) among investors in the group is $0, because the winners were paid out by investors who lost money.

- Negative sum game. The amount of money flowing out to investors is less than what investors put in. There is a net loss among the group. While you may have some individual winning investors, the group as a whole has lost money. This is a negative expectancy … investors lose money on average. Any winning investors were paid out by losing investors, but the winning investors didn’t get as much money as was originally put into the system.

Now, let’s get into each type of game in more detail. In each game, I’ll outline a hypothetical system of 3 investors, and show how money flows among these investors. I use a small number for ease of illustration…obviously in the real world we’re dealing with millions of investors. But the number of investors is irrelevant…the mathematics of the money flow remain the same whether you’ve got 3 investors or 3 million investors. I’ll then go over some real-life examples.

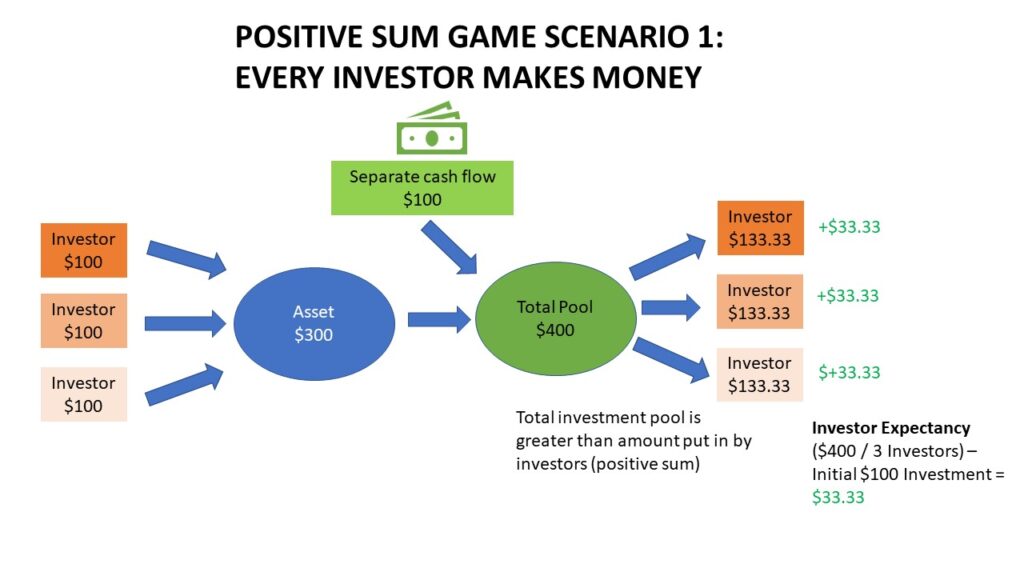

Positive Sum Game

Three investors each put $100 into an asset. Thus, the pool of investment money that’s gone into the asset is $300. The asset also has a separate cash flow (not new investor money) that can go into the asset. Let’s say that separate cash flow is $100. Thus, now the total pool is $400. The total pool is greater than the money that investors put in, making this a positive sum game for investors. The expectancy of the investors in this scenario is ($400 / 3) – initial investment of $100 = $33.3. This is a positive expectancy.

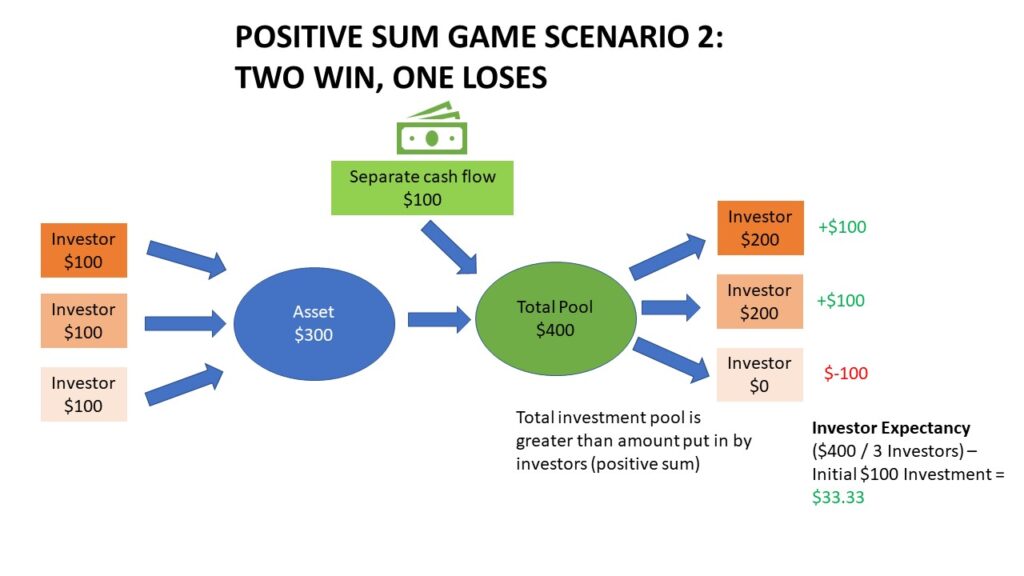

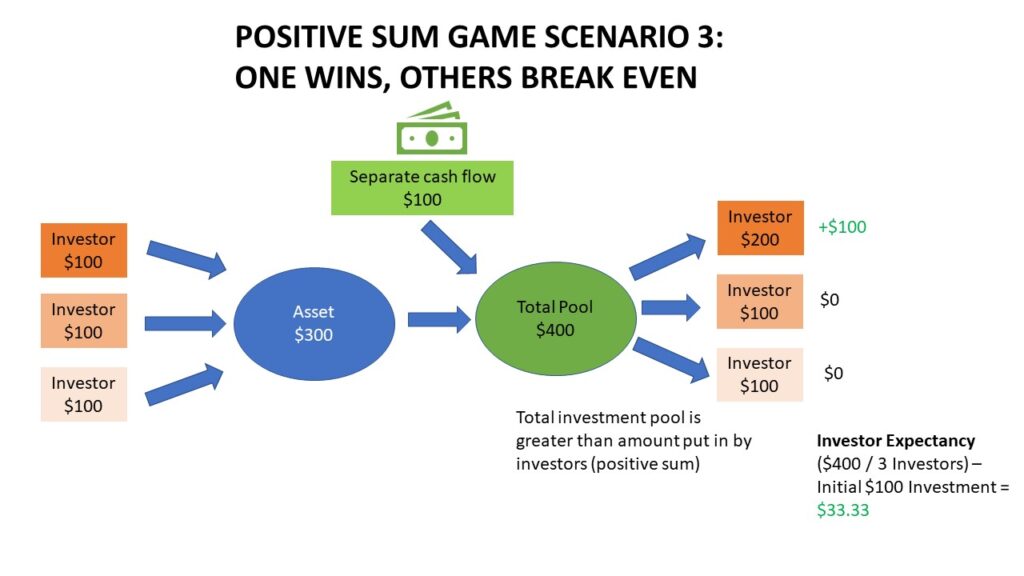

Now, that doesn’t mean every investor makes $33.30 here, or even makes money at all. This is just an average profit. One investor might end up taking $200 from the pool (thus making $100 and giving him a 100% return on his initial investment), while the others only get back $100 and thus don’t make money on their investment. Or, perhaps one investor ends up taking $150 (50% return), and the others end up taking $125 (25% return of each). Or, perhaps one investor takes $300, and the others only get $50. Thus, one investor wins and the other two lose $50 each. But regardless, the average profit is positive.

The key aspect of any positive sum game is that you have money coming into the system that is not new investor money. There are separate cash flows, and investors aren’t just paid out by other investors.

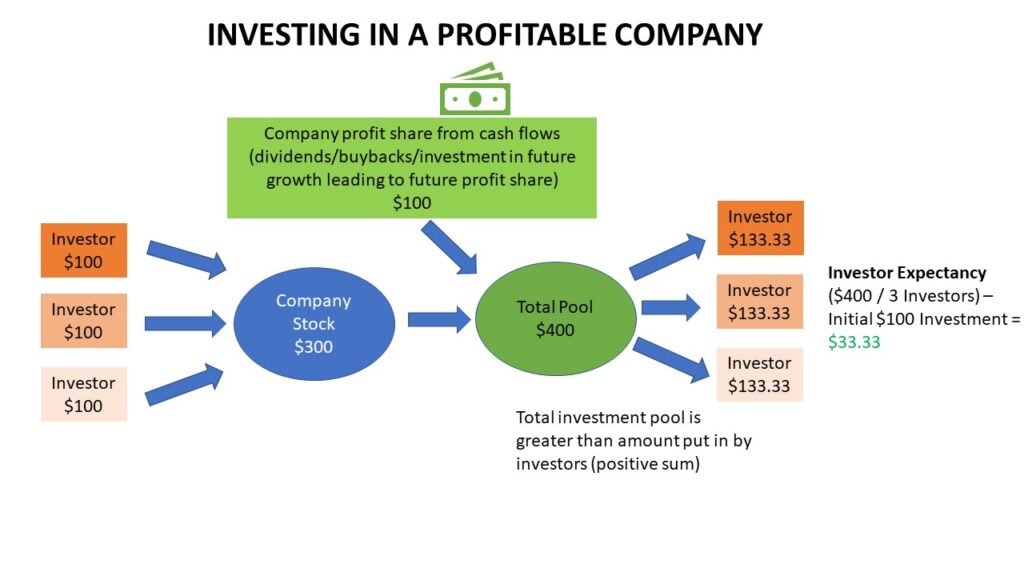

Real Life Example: Investing in a Profitable Company

Investing by buying shares of a profitable company can be an example of a positive sum game. When you invest in a profitable company, you are purchasing the right to a portion of that company’s profits. The company can then share their profits with you in the form of a dividend. Thus, you can make money without having to sell your stock to a “greater fool“. You don’t need new investor money to come in.

A company can also use those profits to buy shares back, which is ultimately returned to you, the shareholder, in the form of share price appreciation (same demand, lower supply = increased price).

A company can also use those profits to expand its operations, leading to growth and future profits, which can then be shared with you down the line.

Note I’m only talking about the game here in terms of investors. Given that companies hire and pay employees with their cash flows, who then turn around and put that money into the economy, there’s more people that benefit other than just investors. There’s a positive sum game in terms of the overall economy. A profitable company also puts out a product that people want and use (this is why they’re profitable!), and thus provides a non-economic net benefit and can be considered a non-financial positive-sum game.

Real Life Example: Investing in Index Funds

This is really just an extension of investing in a profitable companies. Now, you’re just investing in a large group of companies simultaneously. Many of those companies pay dividends. They also all hire employees and are part of the entire economy. They tend to grow with the economy and the overall population. Now, that’s not to say that the overall stock and bond market is always tied to the economy. You can have stock market bubbles where things can get detached from reality and economic output (like the NASDAQ bubble in 1999, or the recent bubble in tech stocks), and the game becomes more zero sum. And actions by the Federal Reserve can impact how the stock market relates to the economy (such as how quantitative easing can influence stock market prices). But overall, over very long periods of time, the overall stock market tends to be a positive sum game, with a positive expectancy for the average investor.

Zero Sum Game

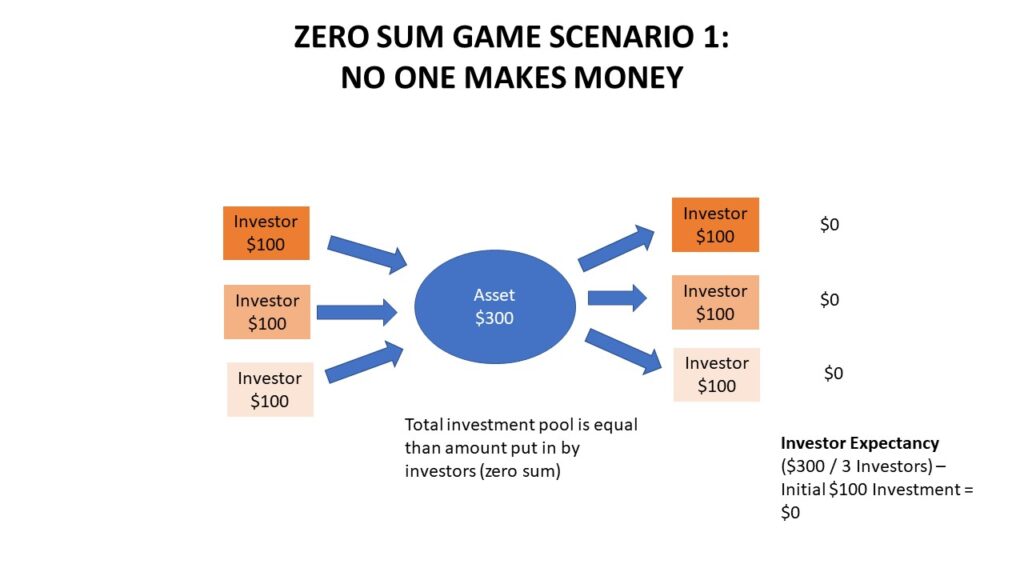

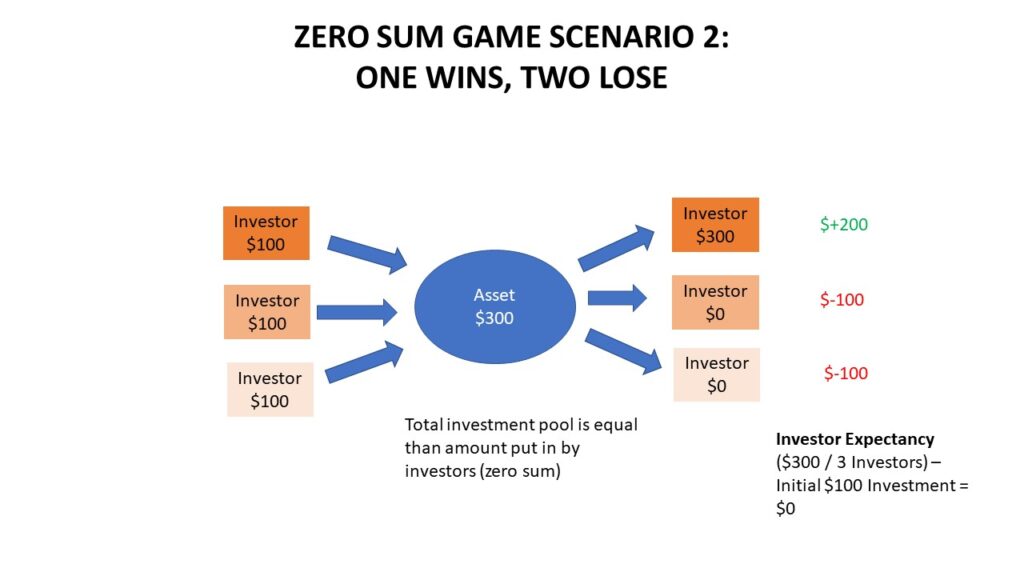

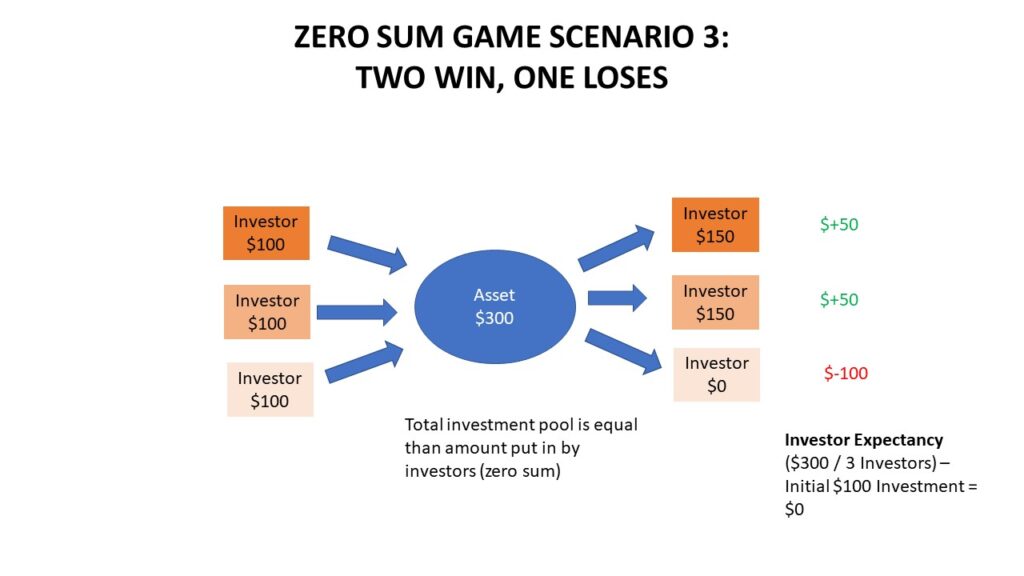

Three investors each put $100 into an asset. Thus, the pool of investment money that’s gone into the asset is $300. There is no other source of money inflows. There is only $300 total available to all the investors. The amount of money that can come out is the same as the money that went in. This is a zero sum game.

The expectancy of the investors in this scenario is ($300 / 3) – initial investment of $100 = $0. This is a zero expectancy. The average investor will not make or lose money. Any winners must be paid out by losers. For example, one investor might take $300 out of the pool (making $200 off his initial investment), while the other two lose $100. Or two investors take $150 each (making $50 off initial investment), while one loses $100.

Real Life Example: Poker

While poker is not an example of an investment, it’s one of the easiest illustrations of a zero sum game. Each player puts money in the pot. One player ultimately wins the money from that pot. The other players lose. The winning player is paid out by the losing players. The amount of money that came out of the pot is the same as the money that went in.

Real Life Example: Day Trading

Day trading is a zero sum game. Any money that one trader makes is money taken from other traders. For example, all of the money I’ve made through day trading is money I’ve taken from other traders. I’m basically a professional poker player playing a giant game of poker with thousands of other players. We are all competing against each other to take each other’s money. This is why, despite numerous requests, I’ll never teach my exact trading strategies to others. I would simply be giving away my edge and giving someone a better ability to take my money. This is also why you should be wary of anyone who is trying to sell a specific trading system. If the system works so well, why would that person be giving the edge away? Most likely the system doesn’t work well and the person is just trying to make money off of selling education systems or off of subscribers. The best trading educators teach general concepts (like InvestorsUnderground), but ultimately leave you to do the hard work of getting the specifics. And no matter how hard you work at day trading, you may not be successful. Since it’s zero sum, not everyone can win no matter how hard they work. Statistics show that most day traders lose money, and less than 1% can consistently make money over the long run. This is why I usually steer people away from day trading despite my own success with it. And if, after all these stats, you still want to be a day trader, make sure you read Michael Goode’s excellent series on it.

Real Life Example: Bubble Assets/Unprofitable Companies/Meme Stocks

Investing in any bubble asset, unprofitable company, or meme stock (like AMC or GME) is going to be a zero sum game. Since the underlying cash flows of the company are insufficient to help pay out investors, the only way for an investor to make money is to sell the asset to a “greater fool.” Thus, one investor’s gain is another investor’s loss. For example, anyone who made money on AMC by cashing out when it had skyrocketed well above 20 was paid out by people who bought the stock at those high prices and are now sitting negative on their investment. In fact, AMC insiders like the CEO made nearly $1 billion dollars by selling into the retail frenzy.

So you know who’s down nearly $1 billion now? That’s right, all of those retail bagholders who bought into the frenzy. The only thing they got out of it was an NFT of a medal.

This is why you should be wary of when you hear about people who made money on some bubble asset like the recent meme stock craze. Anyone who made money was paid out by losers. However, due to survivorship bias, you usually only hear about the winners. It can make it seem like investing in these bubble assets is a good idea, especially when you see the skyrocketing prices. But you don’t hear about all the losers. A similar thing happened with the 1999 tech bubble. You’ll hear about people who made fortunes during that time. But you don’t hear about the massive amounts of people who lost fortunes during that same time. If you want to read some interesting stories of people who lost a lot of money during that time, check out these tweets from @mailboxymoney6 here, here, here, and here).

Negative Sum Game

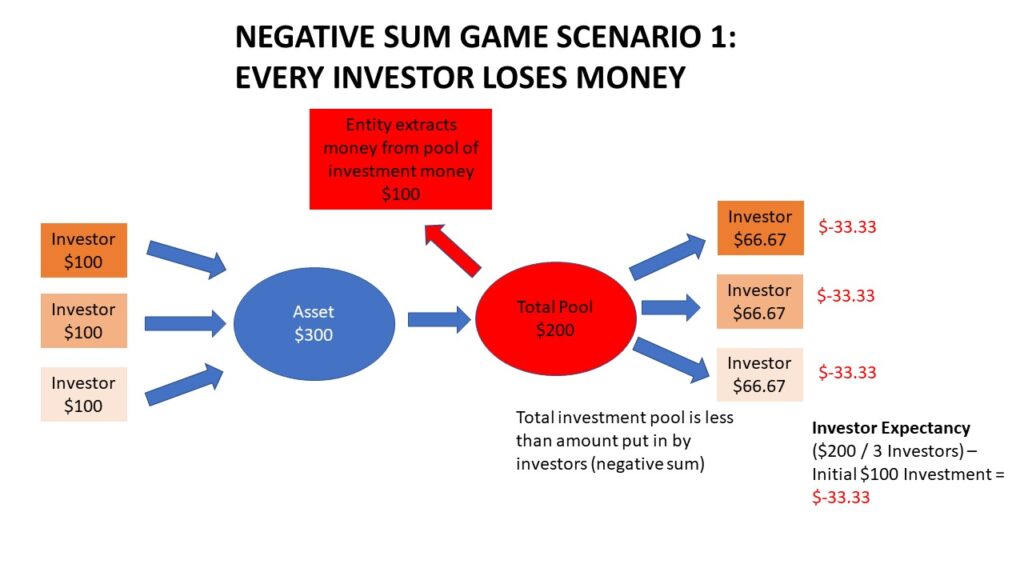

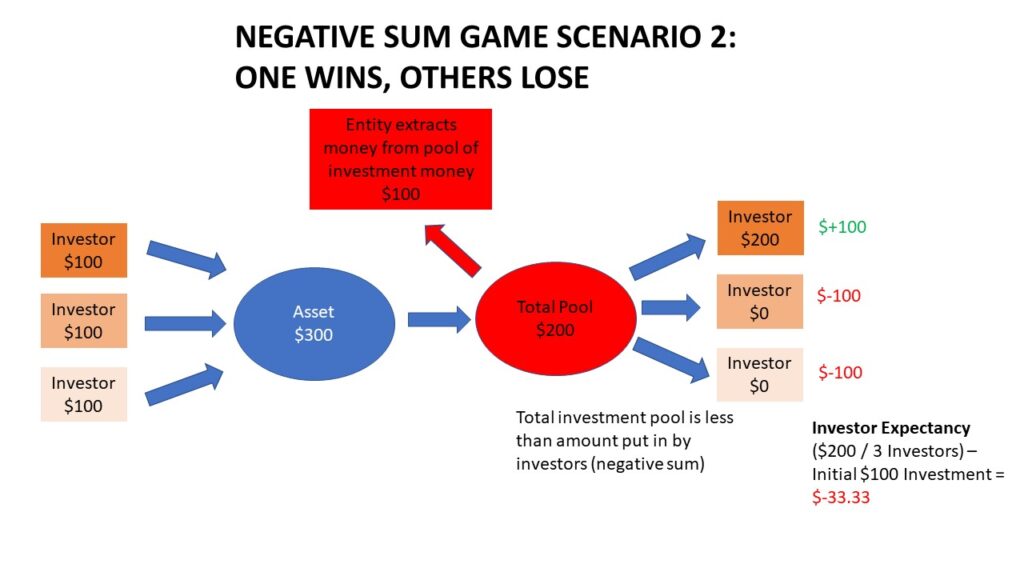

Three investors each put $100 into an asset. Thus, the pool of investment money that’s gone into the asset is $300. There is no other source of money inflows. There is also an additional source of outflows other than investors…a non-investor(s) taking money from the asset. Let’s say this non-investor takes $100 from the pool. Now, the pool of investment money that is available to investors is $200. That’s $100 less than the total money that was put in. Investors as a whole can only be paid out less money than they put in. This is a negative sum game.

The expectancy of the investors in this scenario is (($300 – $100) / 3) – initial investment of $100 = -$33.33. This is a negative expectancy. The average investor loses money. Now, that doesn’t mean everybody loses money. Like a zero-sum game, you can have winners paid out by losers. But even though you may have some winners, the average investor loses. For example, one investor might take the remaining $200 out of the pool (making $100 off his initial investment), while the other two lose $100. You have more losing investors than winning investors in a negative sum system.

Negative sum investment games generally aren’t sustainable over the long run (while they can go on for remarkably long periods of time, they usually come to an end at some point). This is because they completely depend on recruiting new investor money into the game to keep going. Since there is an entity siphoning money out of the investment pool, you have to constantly bring in greater fools to be able to pay out some investors. However, the supply of greater fools is not infinite. At some point, you run out of greater fools, and investors can no longer be paid out. Money continues to get siphoned out of the system until it collapses.

Real Life Example: Ponzi Scheme

A Ponzi scheme is a negative sum game for investors. First, there is only one source of money inflows (new investors). The only way investors can be paid out is through money from other investors. This would be zero sum, but the people operating the Ponzi scheme are siphoning some of the investors’ money. Thus, the pool of money to pay out early investors is less than what was put in. The operators of the Ponzi must continuously recruit new investors into the scheme to keep it going so they can keep paying the early investors and also so they can hide the Ponzi. These schemes can go on for long periods of time…Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme went on for over a decade. Ultimately, though, they aren’t sustainable as new investors eventually dry up (assuming the Ponzi is not exposed before that).

Real Life Example: Crypto

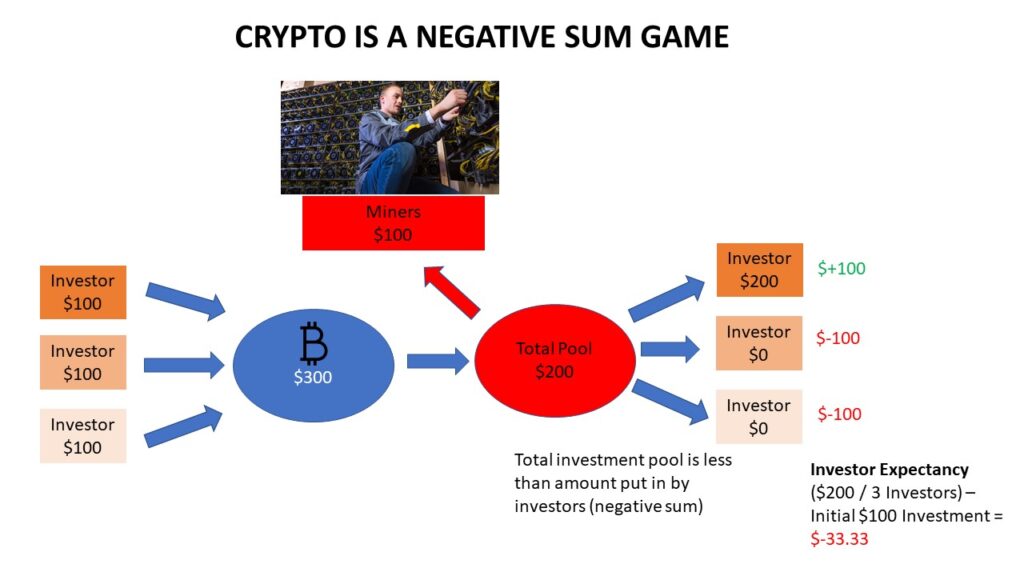

Crypto is a negative sum game for investors. First, there is only one source of money inflows (new investors). Unlike stocks, there is no underlying company with its own separate cash flows. Crypto tokens are just empty greater fool assets. Because there is only one source of inflows, crypto can never be positive sum. Anyone who makes money in crypto must be paid out by someone losing money in crypto.

You might then ask, “Doesn’t that make crypto zero sum?” No. It is negative sum because there is an additional source of outflows: crypto miners. Miners are rewarded with crypto, and thus when miners extract crypto from the pool and sell crypto to pay their electricity bills, they are taking money out of that pool…the money investors have put in. Thus, the aggregate amount of money in the pool available to crypto investors is less than aggregate amount of money that was put in.

This is why crypto has often been compared to a ponzi scheme. They are both similar in money flows. They both have only a single source of inflows, and they both have a non-investor taking money from the pool. They both depend on recruiting new investors to keep things going. But they are both unsustainable because the pool of new investors is not infinite, and the system eventually collapses because investors keep competing for a smaller and smaller pool of money. In fact, crypto miners create the risk of the crypto miner death spiral (which would be a cool death metal band name), where the price of crypto falls below production costs and forces miners to sell (two such death spirals have happened in the past…December 2018 and March 2020). Estimates vary where that death spiral point is, ranging anywhere from $17K to $34K.

I’ve heard some people say, “Well, that’s just true for shitcoins. Bitcoin and Ethereum are great investments. They’ve been around the longest and have the most money in them.” However, all crypto tokens share the same negative sum structure. The market cap or age of the tokens is irrelevant. When you have a zero sum game of empty tokens that have separate entities (miners) extracting money from the investment pool, then it mathematically must be negative sum.

When you have a zero sum game of empty tokens that have separate entities (miners) extracting money from the investment pool, then it mathematically must be negative sum.

One person tried to tell me that she was invested in crypto for the long term, and thus it wasn’t negative sum. She thought that only the time frame mattered, comparing short term trading of stocks (zero sum) to long term index fund investing (positive sum). However, it’s not the time frame per se that changes the game you’re playing. The reason why long term investing is positive sum, while short term trading isn’t, is because with short term trading, the time frame is too short for a company’s separate cash flows to matter. For example, dividends don’t matter if you’re a day trader, but they matter if you’re a long term investor. You can also have instances where you initially invest in an unprofitable company (zero sum) that eventually becomes profitable and rewards shareholders with those profits (positive sum). Thus, holding for the long term in this case can transform a zero sum game into a positive sum game. With crypto, however, there is no underlying company and no separate cash flows. Thus, crypto will always be negative sum, whether you hold your crypto for 10 days, 10 months, or 10 years. You still can only make money by selling to a greater fool, and during all that time you’re holding, miners are continuing to extract money from the investor pool. Crypto is very much like a rigged poker game where a referee is constantly taking money out of the pot. And don’t let the large market cap or huge rise in price over the past few years fool you. The price of crypto is largely fictional, and winners can still only be paid out by multiple losers. The primary winners in crypto are whales who were in early, exchanges, and miners.

Crypto will always be negative sum, whether you hold your crypto for 10 days, 10 months, or 10 years.

And what about some of those crypto millionaires that you hear about, like the Dogecoin millionaire? Remember that since it’s a negative sum game, unrealized gains aren’t true gains. If someone hasn’t cashed out their crypto, they haven’t actually made any money (as of writing this, that Dogecoin millionaire guy still hasn’t cashed out from what I understand, and his unrealized profits have fallen substantially). The only way to make money is to cash out, which means other people will have to take the loss. But due to survivorship bias, you rarely hear about the losers, even though mathematically there will be way more losers than winners in crypto due to the negative sum nature.

Due to survivorship bias, you rarely hear about the losers, even though mathematically there will be way more losers than winners

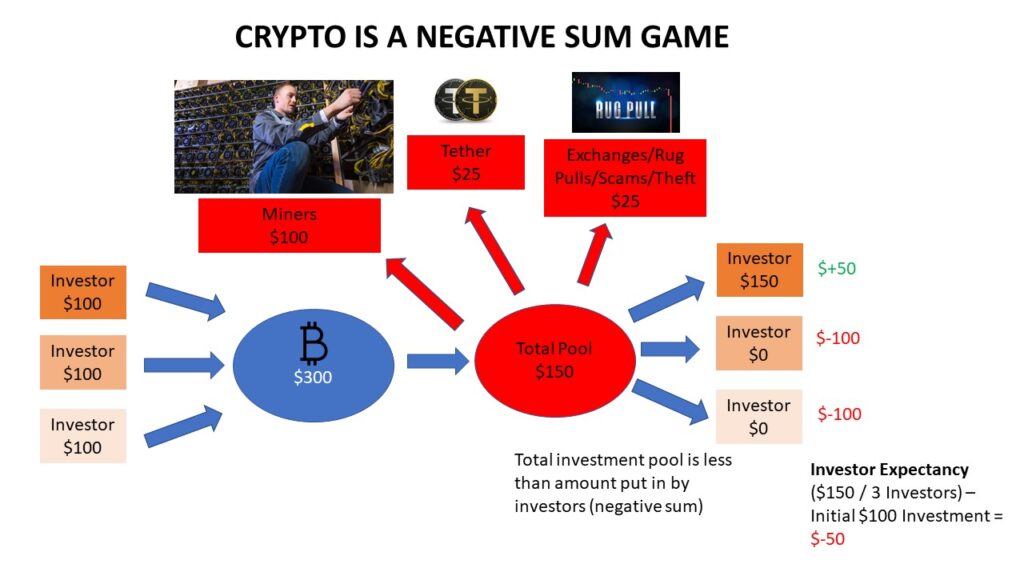

Miners aren’t the only things that make crypto negative sum. The stablecoin Tether is used for approximately 70% of all transactions in the crypto ecosystem. You can think of Tether as casino chips; you trade your real $ for Tether, and then buy/sell crypto with Tether. However, the problem with Tether is that it’s not backed 1:1 by real money. Thus, the chips people are playing with don’t represent real $, which has been siphoned out of the crypto ecosystem and replaced with Tether. This is also why crypto prices are mostly fictional. For example, the current real price of Bitcoin as of writing this is not $36K in real dollars. It is below that; for example, GBTC, the Bitcoin trust that does not involve Tether, is trading at about 30% below NAV as of writing this.

Given that the crypto markets are unregulated, they are also full of rug pulls, scams, and front-running/manipulative tactics by exchanges. All of these contribute to the negative sum nature.

It can be argued that the negative sum nature of crypto goes beyond the negative investor expectancy. The massive energy costs and hardware waste for negative sum assets that are primarily used for speculation means there are negative externalities that impact non-speculators and the general population. We’ve already seen some of these negative externalities through overstrained power grids and chip shortages.

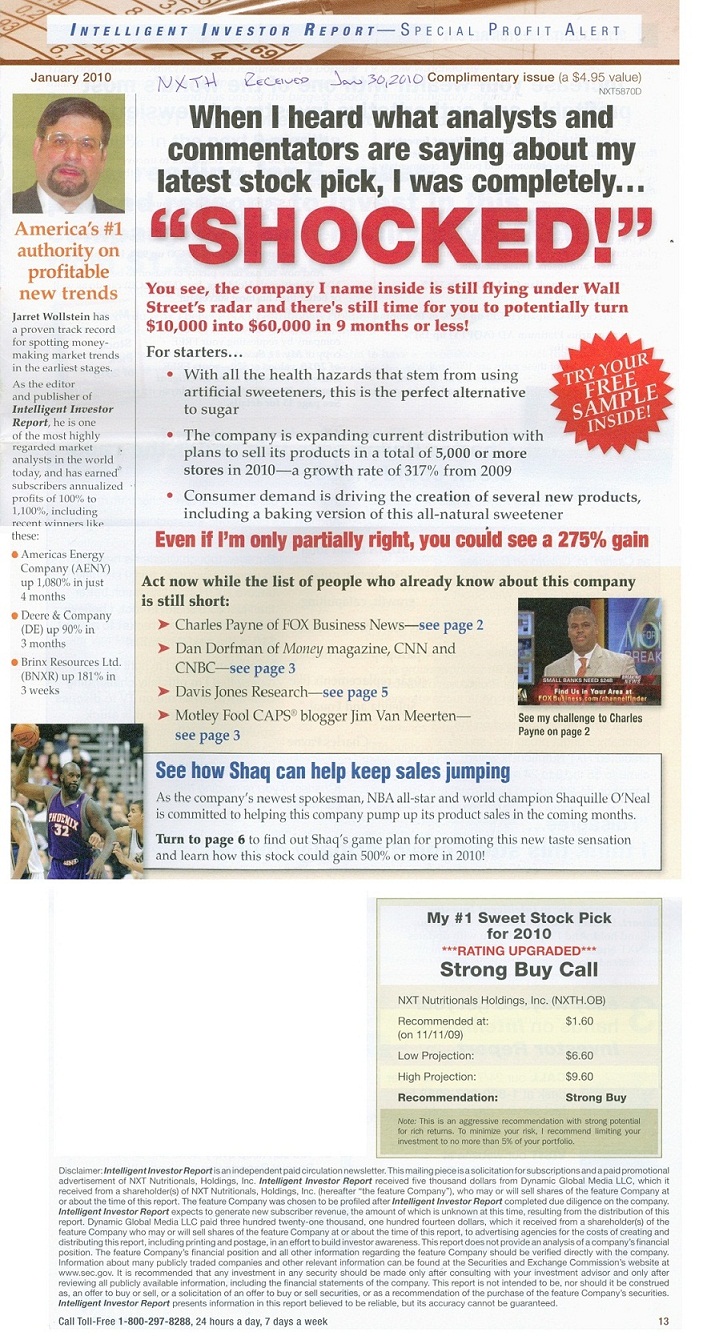

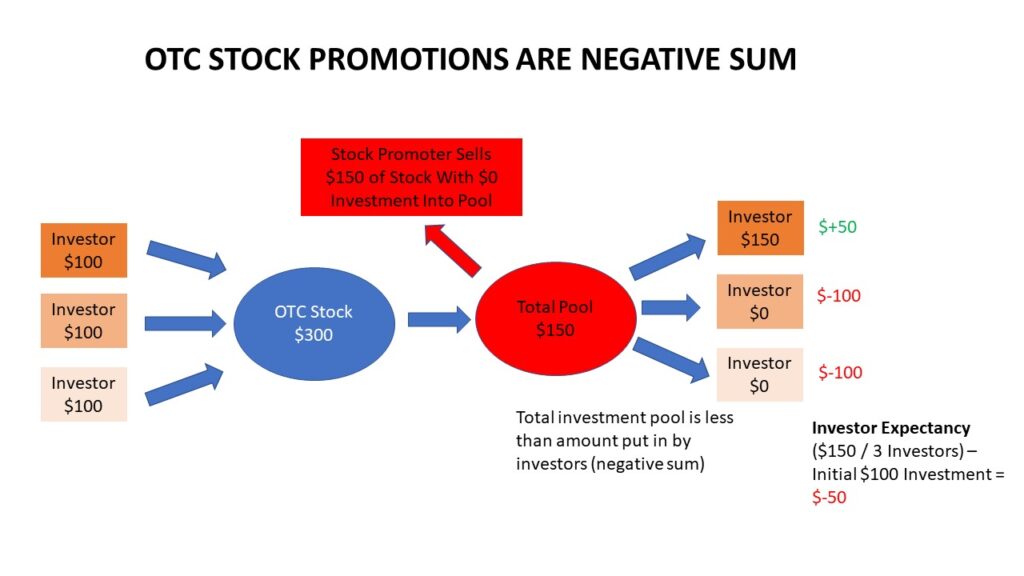

Real Life Example: OTC Pump & Dump Paid Stock Promotion

While you don’t see them much anymore due to SEC crackdowns, paid stock promotions were quite common on the OTC markets a decade ago. This is where a group of insiders, who have a large number of shares of a penny stock for no cost, pay for the stock to be promoted either through hard mailers or through internet ads. This paid stock promotion encourages people to start buying the stock.

The stock promoters may also engage in manipulative trading techniques like wash trading (something that is also quite common in crypto … for other similarities between crypto and OTC penny stocks, check out my post here) to create the appearance of interest in the stock. People start to buy the stock. But who are they buying the stock from? The insiders who got their shares for free. Eventually, the insider finish selling their shares, and the stock promotion stops. Suddenly there is no one left to bid on the stock, and it collapses, leaving all of the retail holding the bag, while the insiders walk away with millions.

This is a negative sum game. Investors are putting their money into the stock. However, the insiders got their shares for free. They never put any money into the pot. They are only extracting from the pot. Thus, the insiders are being paid out by the investors. Yes, a few investors who are smart enough to exit before the dump can get out with a profit, but that only comes at the cost of another investor losing. In aggregate, the amount of money that investors can extract is much less than what they put in.

Know What You Own

The bottom line is that you really need to truly understand what you own. If you’re going to put your money into something, understand what type of game you’re playing, and act accordingly. Understand where money is going, and who the primary winners and losers are most likely to be. If you understand money flows and the game you’re playing, you’ll be more likely to make money and less likely to lose money. As the old saying goes:

God give me the strength to invest in positive sum games, trade zero sum games, and avoid negative sum games, and the wisdom to know the difference.

– Moi

Disclosure: Due to the negative sum nature and system risks in the crypto ecosystem, I have a small MSTR short and some long-dated BITO puts. I am also an InvestorsUnderground affiliate and receive a commission for anyone who signs up for their services through links on my site.

Thank you for the write-up James. I enjoy reading your content. I’ve been learning to trade for the past 6 months and have, religiously, logged all my trades. Additionally, I’m learning with a cash (non-leveraged) account.

Your articles help me maintain perspective in a highly emotional endeavor. Please keep them coming.

FYI. I found you through Layne and Holly’s podcast interview. I loved Dr. Mike’s Photoshop work of you with your dairy check. That dude is funny.

Thank you Joshua! Glad my articles have helped you.

The photoshop was something I had done…Mike just reposted it. But yeah, Mike is a funny dude!